At Emerge Center Against Domestic Abuse (Emerge), we believe that safety is the foundation for a community free from abuse. Our value of safety and love for our community calls us to condemn this week’s Arizona Supreme Court decision, which will jeopardize the wellbeing of domestic violence (DV) survivors and millions more across Arizona.

In 2022, the United States Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade opened the door for states to enact their own laws and unfortunately, the results are as predicted. On April 9, 2024, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled in favor of upholding a century old abortion ban. The 1864 law is a near-total ban on abortion that criminalizes the healthcare workers who provide abortion services. It provides no exception for incest or rape.

Just weeks ago, Emerge celebrated the Pima County Board of Supervisors’ decision to declare April Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Having worked with DV survivors for over 45 years, we understand how often sexual assault and reproductive coercion are used as a means to assert power and control in abusive relationships. This law, which predates the statehood of Arizona, will force survivors of sexual violence to carry unwanted pregnancies—further stripping them of power over their own bodies. Dehumanizing laws like these are so dangerous in part because they can become state-sanctioned tools for people using abusive behaviors to cause harm.

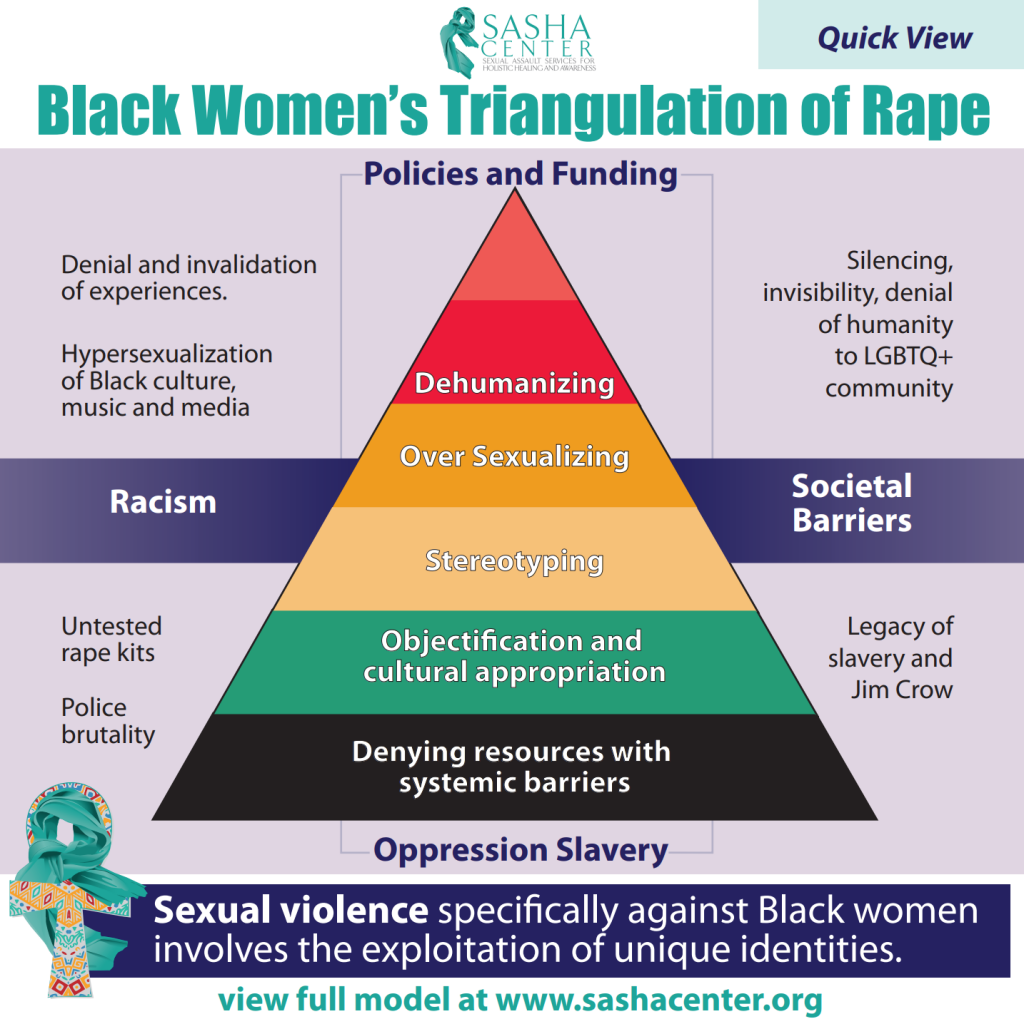

Abortion care is simply healthcare. To ban it is to limit a basic human right. As with all systemic forms of oppression, this law will present the greatest danger to the people who are already the most vulnerable. The maternal mortality rate of Black women in this county is nearly three times that of white women. Moreover, Black women experience sexual coercion at double the rate of white women. These disparities will only increase when the state is allowed to force pregnancies.

These Supreme Court decisions do not reflect the voices or needs of our community. Since 2022, there has been an effort to get an amendment to Arizona’s constitution on the ballot. If passed, it would overrule the Arizona Supreme Court decision and establish the fundamental right to abortion care in Arizona. Through whatever avenues they choose to do so, we are hopeful that our community will choose to stand with survivors and use our collective voice to protect fundamental rights.

To advocate for the safety and wellbeing of all survivors of abuse in Pima County, we must center the experiences of members of our community whose limited resources, histories of trauma, and biased treatment within the healthcare and criminal legal systems puts them in harm’s way. We cannot realize our vision of a safe community without reproductive justice. Together, we can help return power and agency to survivors who deserve every opportunity to experience liberation from abuse.